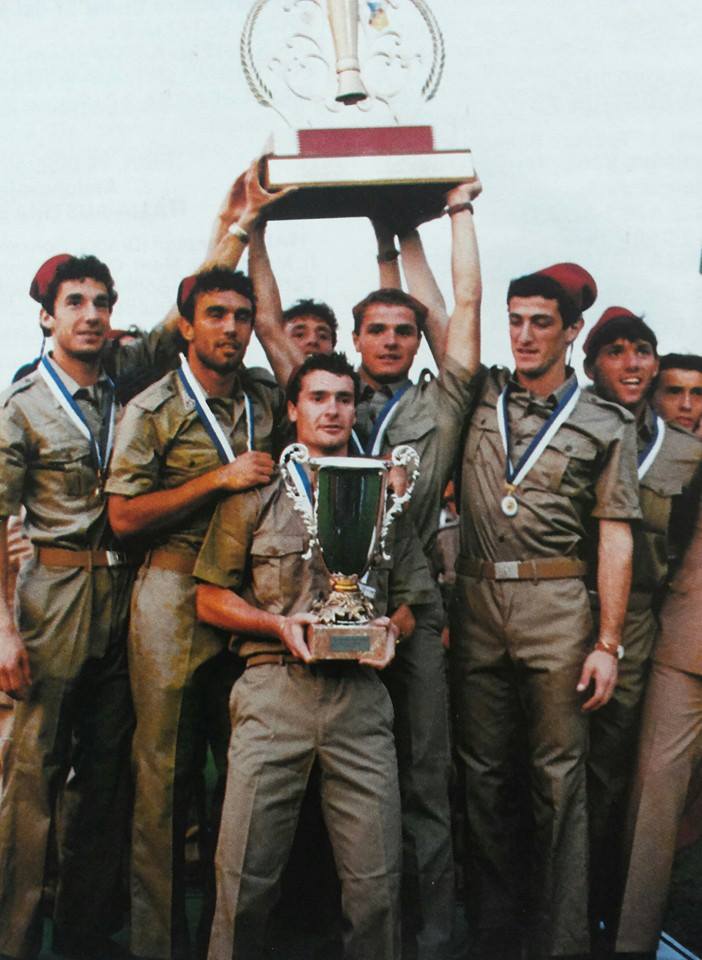

Vialli (centre) celebrating a goal with Sampdoria teammates Roberto Mancini (left) and Graeme Souness (right)

Some footballers really do seem to have it all on the surface: fortune, fame, success, mansions, the partner of their dreams, and above all, a job playing the sport they love, more than almost anything else in life, on a daily basis… But even so, tragedy can befall upon anyone. A terrible disease, such as cancer, after all, does not discriminate against any person, whether they are wealthy or poor. At the beginning of the year, unfortunately former Italian footballer Gianluca Vialli became another one of its victims. Only a few years ago, in 2018, he had shockingly revealed that he had successfully overcome a year-long battle with pancreatic cancer, and seemed to be recovering well even into April 2020. But unfortunately, in December 2021, only months after he had celebrated his role in Italy’s Euro 2020 victory over England (held in 2021, due to the COVID-19 Pandemic) as part of his friend and azzurri manager Roberto Mancini’s coaching staff, specifically as delegation chief, the disease reared its hideous face and returned once again. Despite his resolve to continue treatment, and his valiant attempts to fight the disease, all while still retaining his post, Vialli officially stepped from his role a year later, in order to focus on his battle with pancreatic cancer. Gianluca sadly passed away only a few weeks later, on 6 January 2023, at the age of 58, at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London, where he had initially undergone a seemingly successful treatment during his first struggle with the disease in 2017.

Without wanting to resort to outdated or toxic, hyper-masculine stereotypes, it was clear that Vialli had always been a fighter and a tenacious leader throughout his football career, having even performed national service in the Italian military while still a professional player; his name was naturally synonymous with competition, victory, and success, with his former Juventus team-mate, Italian full-back Moreno Torricelli, once nicknaming him a “warrior.” But unfortunately, this was one battle that he could not win, however hard he fought. On the pitch, he was one of the most determined and successful footballers of all time, being one of the few players to have won the three major UEFA Club Competitions during his playing career, on top of several domestic honours in both Italy and England: the Cup Winner’s Cup (in 1989 with Sampdoria, and once again in 1998 with Chelsea); the UEFA Cup (in 1993, with Juventus); and the Champion’s League (in 1995, with Juventus once again, as club captain). A tremendous athlete and a prolific goalscorer, he became an idol to the fans of all three clubs due to his many spectacular goals, decisive performances, success, and leadership, establishing himself as one of the best strikers of the Serie A golden age in the 80s and 90s; he was later also one of the first foreign star exports to move to the newly established English Football Association Premier League in the mid-90s, contributing to the development of the league following its decline after the five-year 1985 UEFA ban on English clubs from European club competitions, which was implemented as a reaction to the role English football hooligans among Liverpool’s fans played in the tragic Heysel Disaster in the lead-up to the European Cup final against Juventus. Vialli’s success and popularity in England allowed him to achieve international stardom even into his later career, where he spearheaded the front-line of an entertaining pre-Roman Abramovich Chelsea side, which also featured several other talented but ageing Italian players, such as Gianfranco Zola and Roberto Di Matteo, who were brought in to realise manager Ruud Gullit’s vision of Chelsea playing what he had once coined “sexy football.” Like many other fans, it was difficult for me not to fall in love with this gripping, Italian–flavoured Chelsea side, and Vialli in particular, who instantly captured our hearts with his goals and spirit, and he even became a cult hero for the club. He later also had a fruitful spell with the Blues in both domestic and European competitions as a coach, which is particularly impressive considering that at the time, Chelsea were not yet the super-club that came to dominate English and European football under the ownership of the aforementioned Russian billionaire and oligarch.

What Made Vialli so Special?

It is difficult to describe what truly made Vialli such an incredible striker to younger fans who have grown up watching other brilliant, but more prolific, top strikers in the current game, such as Robert Lewandowski, Luis Suárez, or Karim Benzema, among others, who are also arguably even more ruthless finishers in front of goal than Vialli was. Although the Italian number nine still managed an impressive tally just shy of 300 career goals in over 700 appearances across all professional and youth competitions (in total he scored 259 goals in 673 appearances across all club competitions at professional level, with 16 goals in 59 senior appearances for Italy), his goalscoring statistics seem to pale in comparison to the top strikers of the current generation, as he never managed to score 20 league goals or more in a given season (the closest he came was in 1990–91, when he scored 19 goals in Serie A), and only managed more than 30 goals in all club competitions once, during the 1988–89 season with Sampdoria (33 in total). However, it would be reductive to judge Vialli based on statistics alone. After all, Serie A of the 80s and 90s, a league in which he was regarded as one of the best in his position, was not like many leagues today. It was certainly the place to be at the time for a footballer, and clearly the best and most competitive league in the world, with Italian sides dominating the three main UEFA Club competitions, and the league boasted a plethora of attacking, creative, defensive, and goalkeeping talent, and several strong sides competing for the title each year (such as the so-called “seven sisters“). However, despite the undeniable technical and physical qualities of many of its players, it was also quite a defensive-minded and tactical league, with many games being high in quality, but slower-paced and low scoring as well in comparison to other top European leagues (to give an idea of what it was like, legendary Argentine playmaker Diego Maradona won the capocannoniere award with only 15 goals for Napoli in 1987–88, while Capello’s Milan won the 1993–94 scudetto by scoring only 36 goals in 34 games, while conceding only 15). The back-pass rule, and the two-point per win regulations – both of which were later abolished and altered during the early to mid-90s to favour a more attacking game, in particular after the all-time low goalscoring average at the 1990 World Cup – combined with the fewer teams in Serie A at the time (which resulted in fewer games being played in a given Serie A season than La Liga or the English First Division/Premier League), meant that many of the league’s top forwards and leading goalscorers were not as prolific as attacking players in other top European leagues. Moreover, the offside rule at the time, and the officiating, which was far less strict, often favoured goalkeepers and defenders; as a result, it allowed many tough and aggressive centre-backs, to thrive and freely target and stifle the more talented offensive players with a degree of physical play that would not be allowed in the current game, and which would instead be met with suspension. Some of the most well–known ‘villains’ during this era were defenders such such as Italian stoppers (man–marking centre-backs) Claudio Gentile, Pietro Vierchowod (who was also Vialli’s teammate for a time with both Sampdoria and Juventus), full-back Pasquale Bruno (known as the “animal,” who often clashed with Vialli), or even Uruguayan defender Paolo Montero. This is not to say that football was necessarily more difficult at the time, as each era has had its challenges; it was just different, and therefore not as easy to compare to the current era. But certainly at the time in which he played in Serie A, Vialli was held in high regard by any who had the fortune of watching him.

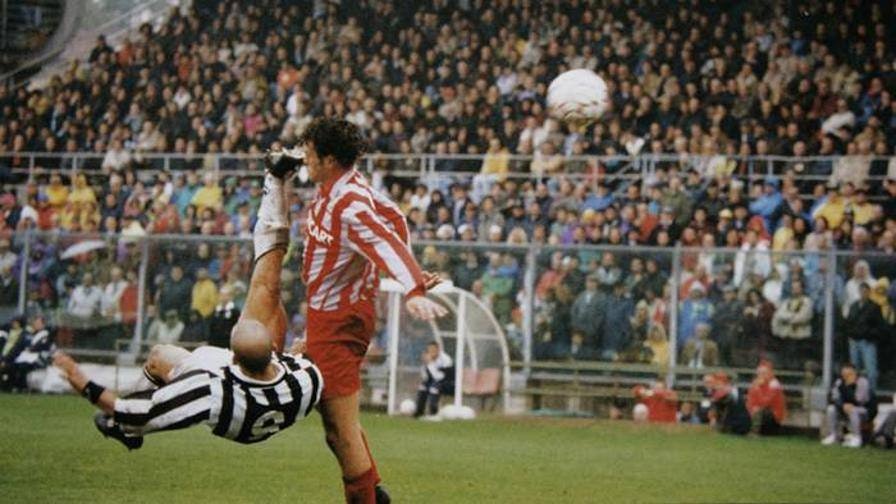

But more importantly, it must be remembered that Vialli was far more than just a striker and a goalscorer, and you really needed to see him to understand how good a player he was. Appropriately nicknamed “Stradivialli” (one of my favourite nicknames for a footballer, as a musician myself; it was a reference to Antonio Stradivari, the famous luthier and craftsman of string instruments, such as violins, from Vialli’s hometown, Cremona) by legendary Italian sports-writer Gianni Brera, and also aptly often referred to as “Michelangelo” (a reference to the celebrated renaissance artist and sculptor) by Juventus president Giovanni Agnelli, Vialli was a phenomenal all–round footballer and athlete as well. He was ahead of his time in his commitment in training, with former footballer Chris Sutton noting that even as a player–manager he “raised the bar and raised the standards of dedication and training” in England. Vialli also stood out in the way he conditioned his body (even in the final years of his life) and looked after his diet and mindset with meticulous care, and was the ultimate professional on the pitch, despite his vices. He wasn’t perfect after all, and was once criticised by his Chelsea manager Ruud Gullit for his reported smoking habit, for example, which he later gave up, admittedly; moreover, although Vialli worked very hard in training and on the pitch, he did also like to live his life, and enjoyed a good lie-in, or a night out at a club! He seemed to have a good grasp of balance, however, as his personal life never seemed to affect his performances, thankfully. Possessing a unique stylistic combination of beauty, brains, and brawn as a footballer, Vialli was a genuine force of nature, a magnificent fusion of sheer power, elegance, spectacular athleticism, skill, guile, & lethal finishing in front of goal. Going by eye test, he was evidently an exciting, complete, and modern striker, being fast, fit, physically strong, agile, and athletic, despite his lean but toned frame; he also had great elevation when jumping, which combined with his intelligent movement, heading ability, made him lethal in the air, even if he wasn’t the tallest of centre-forwards from his era, standing at 1.80m. But when it came to his aerial game, Vialli wasn’t only dangerous with his head; with his incredible shooting power, athleticism, and striking technique, he was particularly gifted acrobatically. Indeed he was known for having a penchant for scoring with some stunning and powerful, bending first-time strikes – usually from volleys – with either foot, from inside or outside the box, and even from set-plays; what is most impressive about his shooting was his consistent capacity to finish well from difficult positions and awkward, unlikely angles, or even while on the run, or when off-balance. This quality of his certainly always captivated me, and made me hold him in high regard; naturally, many who saw him soon became enamoured with Vialli and his flair for the spectacular. Several of his most iconic goals for both Sampdoria and Juventus came from truly stunning and flawlessly executed trademark bicycle kicks, which have stood in the memory of many fans of both clubs. It was the sheer audacity of these truly great goals that also saw Vialli win me over instantly. Whenever he comes to mind today, I still always picture the photograph of his iconic bicycle kick against Cremonese for Juventus in 1994, in which he has been spectacularly immortalised, defying gravity and producing the unexpected against all odds.

Just to give an example of his quality, I’ve included a list of some of his trademark strikes for Sampdoria below (with embedded links), which also often come to mind whenever I think of him:

- His goal in a 2–1 away defeat against Juventus in Serie A on 3 May 1987

- His goals in a 2–2 away draw against Empoli in Serie A on 24 January 1988

- His goal in a 3–1 loss against Milan in the 1988 Supercoppa Italiana on 14 June 1989

- His two volleyed goals in a 4–1 away win against Napoli in Serie A on 18 November 1990

- His acrobatic goal in a 1–1 draw against Arsenal in the friendly 1991 Makita Tournament in London

With Juventus, some of his most memorable goals were:

- His goal in a 2–1 away win against his former club Cremonese in Serie A on 23 October 1994 (arguably his greatest and most famous goal, in my opinion, although I am somewhat biased as a Juventus fan!)

- His goal in a 3–1 home win against Reggiana in Serie A on 20 November 1994

- His goal in a 4–1 away win against Fiorentina in Serie A on 29 April 1995

- His goal in a 1–0 away win against his former club Sampdoria in Serie A on 26 February 1995

- His goal in a 1–0 home win against his former club Cremonese (once again!) in Serie A on 19 March 1995

- His goal in a 1 –1 home draw against Parma (in the second leg of the UEFA Cup final) on 17 May 1995

- His goal against Bari (his final Serie A goal), in a 2–2 away draw on 12 May 1996

Some of his most iconic goals for Chelsea also demonstrated that he hadn’t lost his touch even in his later years; these include:

- His first goal for the club on his debut in a 2–0 home win vs. Coventry in the Premier League, on 24 August 1996

- His strike in a 6–0 away win against Barnsley in the Premier League (one of four goals he scored) on 24 August 1997

- His last goal for the club, in a 2–1 home win against Derby in the Premier League on 16 May 1999

What made Vialli even more entertaining to watch was the fact that he also showed off his athleticism and acrobatic skills in his flamboyant goal celebrations as well (often featuring back-flips), as demonstrated by his celebratory cartwheel after scoring against Inter en route to the scudetto in 1991. Considered to be one of Italy’s greatest strikers, his athleticism, eye for goal, and flair for the spectacular even led him to be compared to legendary Italy striker Luigi Riva in the media, whose role he would later inherit in Italy’s coaching staff, coincidentally (Riva had been a member of Marcello Lippi’s staff when Italy won the 2006 World Cup). Throughout his career, Vialli was regarded by many pundits as one of the best strikers of his generation, and later also as one of the best ever number 9s in the history of Italian football; remarkably, Vialli’s Sampdoria memorable manager Vujadin Boškov even deemed the Cremona-born striker to be superior to legendary Netherlands and Milan centre-forward Marco van Basten, because he was less static, as his movement, speed, fitness, and versatility allowed him to attack from different areas, which made him difficult to contain, even if he felt that Van Basten was superior in the air. But beyond these outstanding physical and tactical qualities, Vialli was also a deceptively skilful forward, who had good ball control and technique, which along with his pace, intelligence, and power, made him difficult to stop on the run, despite not being quite as naturally talented or gifted on the ball as his Sampdoria attacking partner Roberto Mancini, or other Italian creative playmakers (known as ‘fantasisti‘ in Italian football jargon), such as his Juventus teammate, the ponytailed Roberto Baggio. Moreover, despite his advanced playing role, Vialli was also a very generous, energetic, and hard-working player, with tireless stamina and an excellent positional sense; he would often participate in the defensive aspect of the game, by tracking back into midfield to help win back the ball and pressing opponents. He could even drop back to start attacking plays or create chances or space with his passing, vision, crossing ability, and movement, despite mainly being a goalscorer, and was even deployed further back on occasion due to these qualities. His development as a winger in his youth certainly made him a selfless and versatile attacker, and he was capable of playing anywhere across the front-line, and attacking from deep. Indeed, among other things, it was Mancini and Vialli’s ability to both seamlessly interchange the role of provider and goalscorer, which made them such a fantastic duo for Samp, as Vialli himself acknowledged in a discussion with Sky Sports. Additionally, Gianluca’s anticonformist decision to sport an ear-ring, his distinctive shaved head, and the sweatband he wore in his later career, as well as his endorsement deals with Diadora, also made him a popular and recogniseable figure both on and off the pitch. Vialli also stood out for his style, charm, cleverness, and sense of humour in interviews, always articulate and ready to deliver a quip with a sly grin and cheeky glint in his eye, Indeed, one of the elements that made Vialli a genuine star of the game was also the fact that he always understood the importance of players’ relationships with the fans in football, and was even known for donning Ultras (the nickname for groups of fanatical football supporters) bomber jackets. But beyond his qualities as a truly exciting attacking player, it was his fighting mentality, consistency, decisiveness, and charismatic leadership which truly made him an indispensable teammate, especially in big games. It is also these many incredible moments that Vialli produced when it really mattered that still define his legacy. It is therefore of no coincidence that with every club for which he played, Vialli made history, achieving something with them that they had either never done before, or not done in a long time, thus establishing himself as a legendary figure for each of his sides. For example, as a youngster, he led Cremonese to Serie A for the first time, and he helped outsider clubs like Sampdoria and Chelsea to compete with the best teams in both domestic and European football. During his time in Turin, in Baggio’s absence, he was Juventus’s key man, both on and off the pitch, during their first two seasons of the club’s glory era in the mid-late 90s with Lippi, and played a crucial role in the team becoming the best side in the world, after years of playing second fiddle to Arrigo Sacchi’s and Fabio Capello’s legendary Milan sides in both Italy and Europe. And he brought these qualities, in particular his leadership and this winning mentality, with him wherever he went, including in his role as one of Mancini’s assistants with the Italian national side.

Son of a Billionaire

The youngest of five children of a self-made millionaire (or billionaire, if we consider that the Lira was the currency used in Italy at the time), who made his fortune in the industry of prefabs, Gianluca Vialli was born in Cremona on 9 July 1964; he grew up in a wealthy family at the luxurious Castel di Belgioioso in his hometown, Cremona. Interestingly, one aspect of Vialli’s character that several of his former teammates, including Roberto Galia, have highlighted was the fact that, although, unlike many of them, he clearly had a very privileged upbringing (he was often described in a somewhat derogatory manner in the media as “son of a billionaire,” in particular whenever he did not perform well), when it came to football, he was very humble; beyond the glamour, he evidently was a simple person at heart, who had a good head on his shoulders and who always kept his feet on the ground. He was also prepared to work as hard as possible and start from the bottom, without any short-cuts or special treatment. Regarding his wealthy background and its impact on his career, Vialli even once said: “I never wanted anyone to question my attitude on the football pitch.” Ultimately, in the dressing room, he was still just one of the guys. Given his upbringing, it might even seem surprising that Vialli chose to pursue a career in football, when other paths might have been potentially more secure and stable for him financially, but evidently (and fortunately for football fans) his decision to pursue his dreams paid off. Vialli actually started playing football as a child in the local oratory, and later also featured for the Pizzighettone youth side, before joining the youth team of his local club Cremonese at the age of 14. Although he later earned acclaim in the Italian top flight as one of the most lethal and prolific strikers in the league, as I mentioned briefly in the last paragraph, he actually started out playing professional football in his teenage years as a winger for Cremonese in Serie C1 in 1980. His professional football career put an abrupt end to his high school education at the age of 16; given his background, and his parents’ – Gianfranco and Maria Teresa – desire for him to continue his studies, however, he later insisted on going back to obtain his high school diploma specialising in surveying in 1993. In his first year in professional football, Vialli made two appearances for Cremonese during the 1980–81 season as the club earned promotion to Serie B for the first time in its history. After scoring an impressive 10 league goals from this wider position during the 1983–84 Serie B season, helping his side earn its first ever promotion to Serie A, his performances earned him a move to Ligurian side Sampdoria in the Italian top flight the following year. Little did anyone realise at the time that this would be a match made in heaven; indeed, in Genoa, the young winger would transform into one of the most dangerous strikers in Italy, and would form a close relationship with the club’s president, Paolo Mantovani, which would play a role in Vialli’s decision to turn down lucrative offers from the all–conquering Milan run by sordid billionaire, politician, and media mogul Silvio Berlusconi. Vialli left his hometown club for the Ligurian capital having scored 23 league goals in 105 appearances, and 25 in 113 appearances in all competitions during his spell there.

The “Goal Twins”

“We spent a number of years together, and we have relationship that goes way beyond friendship. He’s almost like a brother to me.”

Roberto Mancini on his relationship with Gianluca Vialli

Vialli’s close friendship with former colleague Roberto Mancini actually stemmed back to their playing days together at the Genoa club, where the pair formed a highly formidable attacking duo, largely thanks to Vialli’s goals and Mancini’s assists; due to their combined attacking prowess, they were suitably nicknamed “i gemelli del gol” (“the goal twins,” in Italian) in the press, and are considered to be one of the greatest attacking partnerships of all time, scoring a total of 231 goals together between 1984 and 1992, in addition to winning several titles. Vialli attributes the success of this exciting partnership to legendary Serbian manager Vujadin Boškov, who transformed Vialli from a winger into an out-and-out striker at Sampdoria, with Mancini playing alongside him in a slightly more withdrawn role. Although Vialli was the team’s main goalscorer, Mancini’s role as a second striker allowed him to both score and create goals for his partner; both players established themselves as some of Serie A’s leading forwards. The dynamic duo not only combined well during matches, demonstrating an incredible understanding and strong chemistry, but also maintained a close relationship outside of football, describing themselves as “brothers” (according to Vialli, they only ever argued one time, in training). Together, they led the blucerchiati (“blue–circled,” in Italian, the club’s nickname, a reference to the team’s kit) to their first ever European title in 1990, the Cup Winners Cup, after already reaching the final the previous year, but losing against Barcelona. Vialli finished as top scorer in the 1989–90 edition of the tournament with 7 goals, including both goals in the final victory over Anderlecht; it was indeed in these key moments that Vialli was truly at his finest. He also won three Coppa Italia titles with the Genoese side, scoring a record 13 goals in the victorious 1988–89 edition of the tournament. Aside from the iconic Vialli and Mancini, Sampdoria had a truly wonderful side during this golden era, full of great players, many of whom were Italian, including keeper Gianluca Pagliuca, stopper Pietro Vierchowod, wingers Attilio Lombardo and Ivano Bonetti, as well as Brazilian holding midfielder Toninho Cerezo, among other important team-members, such as Scottish midfielder Graeme Souness and Italian full-back Moreno Mannini. Most significantly, the ‘goal twins’ also led the club to its first ever– and currently only – scudetto during the 1990–91 season (“little shield,” the Italian nickname for the Serie A title, as the league champions sport an Italian tricolour shield on their kit). After the disappointment of the 1990 World Cup, the goal twins, along with several other leading Italian Sampdoria players – fuelled by their limited playing time under Azeglio Vicini – evidently had something to prove; indeed, Vialli also won the capocannoniere title, as the league’s top scorer, with 19 goals. To celebrate the league title, the rebellious and gregarious Vialli (along with several other Samp players) rather strikingly dyed his distinctive mop of thick, dark curly hair platinum blonde! The following season, Sampdoria also went on to reach the European Cup final in 1992, only to be defeated by the so-called Barcelona “Dream Team” at Wembley Stadium in London, U.K., which was managed by legendary Dutch manager and former footballer Johan Cruyff; the Catalan giants won thanks to a late, powerful free kick in extra-time by Dutch sweeper Ronald Koeman, from just outside the box. The final defeat would be Vialli’s last appearance for the club. In total, he scored an impressive 141 goals in 327 appearances across all competition for Sampdoria, with 85 coming in 223 Serie A appearances.

“Don’t believe anyone who tells you football is a war. It’s a sport, a game and you play games with your mates.”

Gianluca Vialli

Juve’s ‘Renaissance Man,’ who Conquered Italy and Europe

Sadly, the following season, the dream attacking partnership was broken up, as Vialli moved to Turin club Juventus in 1992, for a then world record transfer fee of around 40 billion Lire (roughly £12 million at the time). Although much was expected by the club of the potential new attacking duo of Vialli and star number 10 Roberto Baggio, as well as the other dangerous options among the team’s forwards and attacking midfielders (such as Fabrizio Ravanelli, Pierluigi Casiraghi, Andreas Möller, and Paolo Di Canio), Vialli’s form suffered greatly in the league; not only did he struggle with injuries, but did not seem to combine as well with his new teammates as he had with Mancini, Baggio specifically, despite their good relationship off the pitch. Moreover, Vialli was also a victim of his own work-rate, with legendary manager Giovanni Trapattoni frequently tasking him with dropping deep to assist the team defensively, due to his stamina, which saw him often operating further away from the goal than he normally would have; Trapattoni even deployed him out of position in a more creative role in midfield on occasion. Baggio, on the other hand, was instead tasked with fulfilling the majority of both the team’s playmaking and attacking duties, with the team becoming overly-dependent on the number 10’s performances, which was ultimately unsustainable. Trapattoni’s more pragmatic and conservative playing style also likely did not complement Vialli’s goalscoring instincts particularly well. The Italian manager had once been one of the main and most successful proponents of the zona mista or gioco all’Italiana system, which arose from the remains of the defensive Italian catenaccio following its demise after the advent of the more offensive Dutch total football; it therefore sought to combine elements of both systems effectively, namely man–to–man marking and zonal defence. Considering his price-tag, it was rather disappointing that Vialli’s impact was not initially as heavy as was hoped; his goalscoring also suffered, and he failed to hit double figures in the league over the next two seasons (and across all competitions in his second season), also missing out on any domestic silverware. However, he did still contribute to the club’s 1992–93 UEFA Cup title, scoring 5 goals, as well as providing several assists; these include his decisive passes in the the second leg of the semi-finals against PSG, and those in both legs of the final against Borussia Dortmund, including the first of Roberto Baggio’s two goals in the first leg, which proved to be the decider; he was also involved in several other of the team’s goals during the two-legged encounter, which ended in a 6–1 aggregate victory.

Following Marcello Lippi’s appointment in 1994, however, Vialli underwent a rigorous training regime and seemed to undergo both a physical and psychological metamorphosis; as a result, his goalscoring record improved drastically, and he finally gave the Juventus fans what they had been waiting for. In Roberto Baggio’s lengthy absence due to injury, Vialli was not only the main striker, but he also took on the role of club captain and the team’s leader; given his personality, he seemed naturally suited to this role, and also began to have a larger role with the club than the more introverted Baggio. He participated in negotiations with the club’s board of directors and management team, and aided in organising outings for the team, and even forged a close relationship with Luciano Moggi, Antonio Giraudo, and Roberto Bettega, as well as Lippi in particular, whom he even dubbed his “Messiah.” Now increasingly playing in a central attacking role in a 4–3–3 system, and with more support from some key new arrivals in both midfield and defence, Vialli rediscovered his former self: he scored 17 goals in Serie A, as well as 3 in the Coppa Italia, and 2 in the UEFA Cup, for a total of 22 goals in 46 appearances across all competitions, as Juventus won a domestic double. Unlike Trapattoni’s struggling ‘nearly men,’ Lippi’s Bianconeri were an aggressive, dynamic, energetic, physical, and all–action side, who would press their opponents, and who sought to win games by controlling and dominating them, continually attacking, and looking to score goals, while also remaining balanced and organised at the back; indeed, when necessary, they still retained their ability to sit back and absorb pressure only to hit their opponents on the counter-attack. This do or die philosophy evidently suited Vialli’s offensive, hard-working, and swashbuckling style. It was certainly was a risky approach, but after a lengthy title drought, the Turin side were prepared to go out fighting in order to win, and this winning mentality ultimately paid off. Vialli combined well with the industrious and prolific, silver-haired target-man Ravanelli in attack in particular, who had also re-found his prior form under Lippi, but also with Baggio finally, when he was fit, as well as the promising young fantasista Alessandro Del Piero, who replaced the latter in the starting line-up throughout his injury absence. The club even narrowly missed out on a historic treble, losing out to Parma on aggregate (2–1) in the 1995 UEFA Cup final, despite Vialli’s stunning opening goal in the second leg 1–1 home draw. As the team’s leader and key player, no player better epitomised Juventus’s renaissance under Lippi than Vialli, and he played a key role in creating a united team environment. After an incredibly successful season, he even remarkably arranged to have the team’s scudetto celebrations at his family’s extravagant villa!

Without wanting to seem hyperbolic, in hindsight, it seems rather harsh that Vialli was not at least a major contender for the 1995 Ballon d’Or, finishing rather surprisingly in 19th place, well behind his club teammates Del Piero and also Ravanelli. There certainly were better players at the time, but not many of them had a season like Vialli’s. Liberian striker George Weah was certainly a deserving winner of the 1995 FIFA World Player and European Footballer of the Year awards for his prolific goalscoring and domestic cup and Champion’s League performances for PSG, as well as his good form and decisive performances with Milan (and the fact that he became the first African player ever to win these awards made this historic moment all the more wonderful), and Finnish playmaker Jari Litmanen – who placed third – would’ve also been a worthy recipient for his goals and role in Ajax’s Eredivisie-Champion’s League double, but Vialli’s exclusion from the top three is rather astounding. Jürgen Klinsmann‘s brilliant goalscoring performances for Tottenham and subsequently Bayern Münich throughout the entire calendar year instead earned him a rather surprising second place finish in the award, which comparatively seems rather generous, in hindsight, notwithstanding his undoubted quality as a player. Vialli rather shockingly was not even chosen as one of the top 10 finalists for the 1995 FIFA World Player of the Year Award, despite being named World Soccer Player of the Year, with club teammate Baggio making the top five ahead of him, and compatriot Paolo Maldini and German striker Klinsmann finishing in second and third place respectively, followed by Brazilian star Romário in fourth place.

The following season, after Baggio’s departure to Milan, Vialli assumed the role of permanent club captain. During the 1995–96 season, he scored the only goal in the Bianconeri‘s (“Black and Whites,” in Italian, the club’s nickname, a reference to their kit colours) first ever Supercoppa Italiana title victory over Parma, while he netted a respectable 11 goals in the league, although Juve finished runners-up behind Milan. Most significantly, however, he helped lead the club to the Champion’s League title, as Juventus overcame defending Champions Ajax 4–2 on penalties in the final after a 1–1 draw. Although Vialli, rather surprisingly, did not take one of the spot kicks, his leadership and work-rate were on display throughout the match; this was the club’s first victorious campaign in the competition in 11 years, their first title in the Champion’s League era, and only their second overall (in fact, Vialli is still the last Juventus captain to have lifted the coveted ‘Big Ears’ trophy). At last, Vialli finally won the most prestigious European club title at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome after missing out on it four years earlier. En route to the final, Vialli scored, twice, with his only goals coming across both legs of the semi-finals; he netted the opening goal with his knee following a corner in the 2–0 home victory over Nantes in the first-leg, and then scored again during the second leg, later also setting up Paulo Sousa‘s decisive goal to allow Juventus to prevail 4–3 on aggregate. After two years of struggling to rediscover the remarkable player he had once been at Sampdoria, Vialli had finally lived up to his price–tag, establishing himself as one of Juventus’s most important players in his two seasons under Lippi, and is still remembered as a club icon to many Juventus fans, myself included. In total, he scored 53 goals for the club in 145 appearances, with 38 of them coming in 102 Serie A appearances.

Despite Vialli’s success at Juventus, and his iconic status in Italian football, there was, however, also controversy surrounding his time at the Turin club. Two years after Vialli had already left the club for Chelsea, Roma coach Zdeněk Zeman gave an interview with L’Espresso, which was published in the 1998 article “Get Out of the Pharmacy.” In this interview, the veteran Serie A manager rather astoundingly alleged that Vialli and Del Piero’s noticeable athletic and muscular development during their time at the Turin club under Lippi was due to the club’s medical team having supplied illegal performance enhancing substances to its players. Given Juventus’s success at the time, and their reputation as the best club in the world, these allegations certainly tarnished the club’s image and brought into question their European dominance. Consequently, Vialli lambasted Zeman for his comments in retaliation, even calling him a “terrorist” (Zeman later sued him for this remark), and vehemently denied ever taking illicit substances; he even testified when an investigative probe was launched into the matter. The ensuing raid of the club’s medical facilities, in which 281 drugs were found – most of them legal, admittedly, but still a shocking number – led to a trial, in which experts inferred, from old blood analysis reports, that the abnormally high haemoglobin levels of certain Juventus players were due to the banned blood-booster erythropoietin (EPO) having been administered to them. This led to the sentencing of the club’s doctor at the time, Riccardo Agricola, to a fine of €2,000 and 22 months in prison. He was later acquitted of all charges on appeal for insufficient evidence in 2005, however, and the case was later thrown out after the club were cleared of all charges; the final Supreme Court verdict, in 2007, claimed that the distant evidence did not prove any wrongdoing with certainty. Whether or not the club was truly guilty, at least it seems that Vialli and the other Juventus players were unaware of what was happening behind closed doors, and Vialli was not even named among the players who were thought to have taken EPOs by leading haematologist and key witness Giuseppe d’Onofrio. However, this topic was clearly a sore subject for Vialli (in 2012, for example, he took a jab at Zeman’s energetic side Pescara on Twitter, who were dominating Serie B at the time), who regretted his reaction in hindsight, but understandably did not want his professionalism, success, ability, and integrity brought into question. Although it is true that he later admitted that the club’s doctors had given creatine to him, along with other Juventus players, (as was often the case at the time with players of other teams in Italy), it should be noted, however, that while this practice was still controversial, this was not a banned substance at the time. After Vialli’s and Siniša Mihajlović’s deaths, however, there was further controversy when the incident came to light once again following comments made by Vialli’s former Juventus teammate Dino Baggio; the retired midfielder praised Vialli, describing him as a key dressing personality and someone who believed in youth development, but also raised concerns about doping having caused potential health problems to former Serie A players of the 90s; he went on to ask for further investigations to be carried out. His comments sparked public outrage, due to their perceived callousness and irreverence so soon after Vialli’s passing; Baggio later clarified that he had misspoken, however, and stated that he was merely referring to concerning legal supplements that were given to the players during that period, as well as potentially toxic sprays that were used on the pitches.

The Italian Job

Given Vialli’s success in Serie A with two major clubs, at a time when the league was undoubtedly the best in the world, it is possibly somewhat unfortunate that most English and international football fans outside of Italy mainly remember him for his memorable time with Chelsea. He was still admittedly quite brilliant, decisive, and clinical in front of goal in West London, especially in cup competitions, and was arguably even one of the Premier League’s best strikers of the late 90s, living up to his reputation even during the final stages of his career; however, he was cearly not quite the captivating, prolific, athletic, and explosive player he was in his prime in Italy. This might explain, aside from his goalscoring statistics and mixed success at international level with Italy, why he is not always held in as high regard as other leading strikers of his generation.

After moving to London on a free transfer in the summer of 1996, Vialli won the FA Cup in his first season, Chelsea’s first title in 26 years, notably scoring a brace in a 4–2 comeback victory over Liverpool at home in the fourth round; however, his relationship with player-manager Ruud Gullit gradually deteriorated throughout the season, and he began to be left out of the squad. He still finished as Chelsea’s top-scorer with nine goals in the league, including one on his debut in a 2–0 home win over Coventry, as they finished in sixth place; however, he only made a brief substitute appearance in the 2–0 FA Cup final victory over Middlesborough. Following Gullit’s dismissal in February of the following season, Vialli went on to become a successful player-manager for the club himself (something quite rare in contemporary football), becoming the first Italian manager ever to coach in the Premier League. He scored a personal best of 11 Premier League goals during the 1997–98 season, (he was once again the club’s top scorer in the league, alongside Norwegian striker Tore André Flo), including four in a 6–0 away win over Barnsley in 1997, as Chelsea finished in fourth place; most significantly, however, he guided the Blues (the club’s nickname, a reference to the colour of their kit) to a domestic and European double: this included the League Cup in 1998, as well as the side’s second European title ever, and their first since 1971, the 1997–98 Cup Winner’s Cup (during which he scored a brace in a 3–2 second round loss at Tromsø, and later a hat-trick in a 7–1 home win in the second leg against the Norwegian side). As a result, he became the youngest manager ever to win a European club title at the time, at the age of 33 years and 308 days; the record was later broken by future Chelsea manager André Villas-Boas with Porto’s Europa League victory in 2011. Vialli’s 1998 double success was immediately followed by the UEFA Super Cup victory over Champion’s League winners Real Madrid later that year. Vialli subsequently retired from professional football at the conclusion of the 1998–99 season, during which he helped Chelsea reach the Cup Winner’s Cup semi-finals, and finish third in the Premiership – their best placement in the league since 1970 – and qualify for the Champion’s League for the first time ever. Although he did not feature often in league play, he scored 10 goals across all competitions in 20 appearances, with some highlights in the League Cup: these included a hat-trick in a 4–1 home win against Aston Villa in the third round, and a brace in a 5–0 win in round of 16 against Arsenal at Highbury; he also netted the match-winning goal on his final club appearance, a 2–1 home win over Derby on the last day of the season in 1999. In total, he scored 40 goals in 83 appearances for Chelsea, 21 of which were scored in 58 Premier League appearances; rather astoundingly, around 35% of Vialli’s Chelsea goals came as a player–manager.

As the team’s full-time manager, Vialli reached the quarter-finals during Chelsea’s debut campaign in the 1999–2000 Champion’s League, in addition to winning the FA Cup for the second time over Aston Villa, despite a fifth-place finish in the league. Although he started the 2000–01 season promisingly with a victory over Premier League title winners Manchester United in the 2000 Charity Shield, Chelsea’s poor league form and dressing room tensions saw Vialli sacked after only five games. Nevertheless, he departed the club as Chelsea’s most successful manager ever at the time, in terms of titles won (a record since broken by José Mourinho).

“Italian fans are all about results. English fans are more about effort. They want to see the team and the players try very hard. If you do your best, if you sweat in the shirt at the end of the match, win or lose, they will clap you and support you and tell you that the next game will be a better one. You are basically one of the fans. You are an extension of them on the pitch wearing the shirt you are playing for.”

Vialli contrasting Serie A and Premier League fan culture.

Although Vialli went on to pursue UEFA coaching courses in an effort to improve his managerial skills, an unsuccessful spell with First Division side Watford during the 2001–02 season followed, which sadly saw him finish in a disappointing 14th place, which led to his dismissal at the end of the season. After a lengthy legal dispute with the club over his reported unpaid wages for the remainder of his contract, Vialli then took a long and indefinite hiatus from the stress of coaching. He instead worked mainly in the world of business (co-founding sports investment company Tifosy in 2014) and in the media as a pundit; he also started the Fondazione Vialli e Mauro per la Ricerca e lo Sport along with fellow former footballer Massimo Mauro in 2003, a charitable organisation dedicated to raising funds for cancer and ALS research. As a TV pundit, Vialli worked for Sky Sport Italia in particular, but also in England as well, being a member of the BBC Sport Euro 2012 analytical team. It was in the latter role that his popularity persisted, thanks to his eloquence, affability, humour, and insight. I still remember an interesting analysis he made – in flawless English (Vialli was a polyglot, who even had a fantastic grasp of local slang) – while working as a pundit during Euro 2016, regarding England’s struggles to handle the mental pressures of the game at international level (unfortunately I can’t seem to find the clip, but at the time, England had only made the last four of a major tournament once since finishing in fourth place at the 1990 World Cup, a feat they finally repeated in 2018), and its relation to the culture around youth development. He had already raised this issue repeatedly during the 2014 World Cup, and also in his 2006 book The Italian Job, co-written with his friend, pundit Gabriele Marcotti; in his book, he highlighted some of the key differences between Italian and English football during his career, in particular at youth level, noting however that positive changes had been made since he first arrived in England, and that their effects were starting to be noticed.

“Kids in Italy train the way professionals do. I went through it myself, both at my first club, Pizzighettone, and then when I moved to Cremonese at 14. In retrospect I think this is hugely important. A boy’s first experience of organised football affects his vision of the game. And, for a kid in Italy, this means treating football as a job, something to be taken seriously – enjoyed, of course, but in a professional way.

The English boy’s first experience of organised football is different, often in the context of a school team. In Italy, there is practically no football in schools but there are plenty of ‘football schools’. For English kids football is an extension of school – the ‘fun’ part. Nobody is forcing the young Italian boys to join their local football clubs, but once there, they immediately adopt a ‘professional’ – some might say regimented and quasi-military – attitude to it.

The Italians take the ‘real world’ with them on to the pitch at youth level while in England there seems to be – at least where the kids are concerned – a greater sense that the game is just that: a game. It’s a game where kids have fun and – directly or indirectly – learn a thing or two about sporting values.”

An excerpt from Vialli’s 2006 book The Italian Job, co-written with Gabriele Marcotti, comparing English and Italian youth football

Vialli’s Two Lives in “Azzurro”

With the Italy national team, Vialli also enjoyed some success as a player, although to a lesser degree than he deserved considering his club success. This was in part due to competition from many other world class Italian strikers at the time, as well as tensions with a successful but intransigent manager such as Arrigo Sacchi. The pair clashed during a difficult time in Vialli’s career, where he was initially struggling in front of goal following his move to Juventus. As such, the striker only earned his final cap in a 1994 World Cup qualifier against Malta in 1992 (also scoring his final international goal in the 2–1 away win with a trademark flick), and missed out on the 1994 World Cup and Euro 96 squads. The exclusion from the U.S.A. 94 side was also somewhat understandable, given Vialli’s poor goalscoring form at Juventus; however, it is possible that Vialli might have been a more effective strike partner for his more creative Juventus team-mate Roberto Baggio, despite their lack of chemistry on the pitch at club level at times. Indeed a true number 9 was the kind of player that the so–called Divine Ponytail Baggio lacked alongside him throughout the tournament en route to the final; this was especially the case with prolific striker Giuseppe Signori often being played out of position in a more creative role on the left flank, while strikers Daniele Massaro and Casiraghi both struggled to find the back of the net (Massaro scored once in Italy’s final group match, a 1–1 draw against Mexico, while Casiraghi went scoreless). As such, Baggio virtually single-handedly carried Italy through the knock-out stages with his goals; with the number 10 hampered by injury throughout the final, which ended in a penalty shoot-out defeat against Brazil (with Baggio infamously missing the last penalty), no other attacking player seemed to step up for Italy. Given Vialli’s proclivity for deciding big games, maybe if Sacchi had brought him along to the United States, he could have made a difference on this occasion, even when he was not admittedly at his best.

Vialli’s Euro 96 exclusion seems particularly surprising, although admittedly not entirely unexpected when further context is given. After all, Vialli had already refused any further call-ups from Sacchi in 1995, after the manager had picked him for the Italy squad following his resurgence under Lippi at Juventus, a decision Gianluca later stated he regretted, however. Notwithstanding the multitude of talented Italian forwards that Sacchi had to choose from, seeing as Vialli was back to his best and had just won the Champion’s League with Juventus, after already winning a domestic double the previous season, it seems a shame in hindsight that he did not accept Sacchi’s call-ups, especially when the tournament was held in England, and he would go on to play for Chelsea later that year. Without him, Italy ultimately suffered a shockingly disappointing first-round exit in the tournament, despite initially being one of the favourites, having reached the World Cup final only two years earlier.

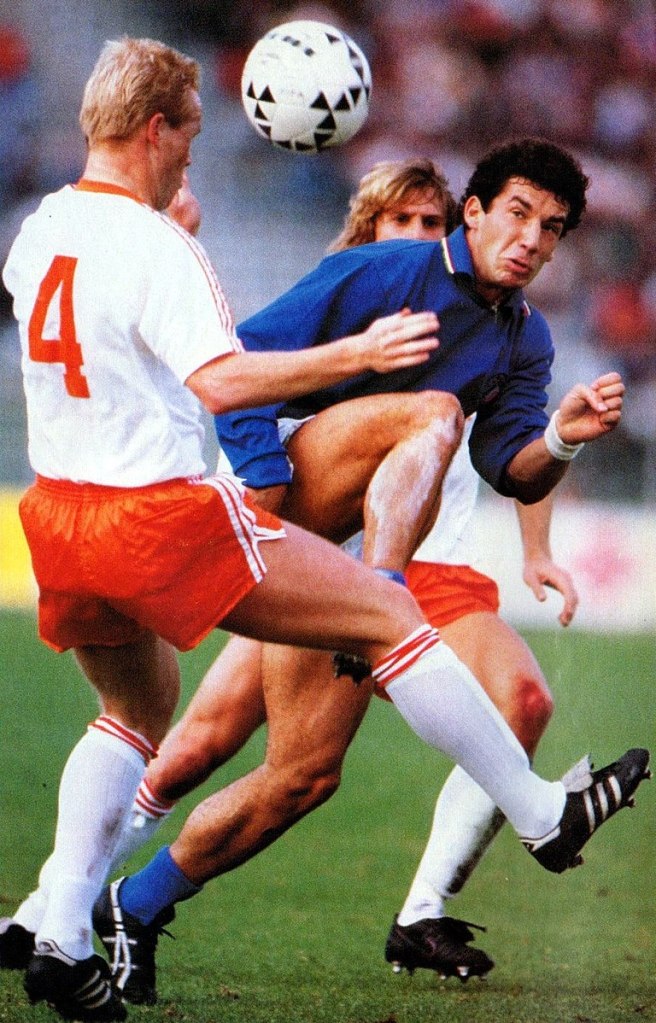

Vialli did also have some international success at youth level initially, however, contributing to the azzurrini’s respective third and second place finishes at the 1984 and 1986 UEFA European Under-21 Football Championships, finishing as top-scorer of the latter edition of the tournament with 4 goals, as Italy lost out to Spain on penalties in the final. He scored a total of 11 goals in 20 appearances for the U21 side. He went on to make his full debut for Italy in 1985 in a friendly loss against Poland, but would only score his first senior international goal the following year, in a Euro 88 qualifier against Malta, later also scoring a spectacular brace, in typical Vialli fashion, in a 2–1 win against Sweden during qualifying. Uniquely, he also rather remarkably won the Military World Cup with Italy in 1987, during his years of national service.In total, he scored 16 goals in 59 appearances for Italy at senior level. Vialli was in strong form alongside his club teammate Roberto Mancini at Euro 88, scoring in a first round victory over Spain en route to the semi-finals, where Italy were eliminated by the Soviet Union; Vialli was even included in the team of the tournament for his performances. He also featured in the Azzurri’s (“Light Blues,” in Italian, a reference to their Savoy blue kit) 1986 and 1990 World Cup squads; he made four substitute appearances in a round of 16 exit in the former edition of the tournament under legendary Italy manager Enzo Bearzot, with Vialli serving as a back-up to star Bruno Conti in the right wing position.

Vialli contributed to Italy’s third-place finish on home soil four years later with several assists, despite going scoreless throughout the competition, and performing below expectations. Although Vialli was initially in Azeglio Vicini’s starting XI at Italia 90, the surprisingly incredible form of poacher and eventual Golden Boot and Golden Ball winner Antonio ‘Totò’ Schillaci throughout the tournament, combined with Vialli’s struggles in front of goal, saw Vialli pushed out of Azeglio Vicini’s starting line-up in the knock-out stages of the World Cup. Moreover, Schillaci’s highly effective link-up with the talented young second striker Roberto Baggio seemed to convince Vicini that theirs was the strongest possible Italian offensive partnership. Indeed, Vialli’s ‘goal twin,’ Roberto Mancini, was even less fortunate, as he failed to make a single appearance throughout the tournament, in part due to the effectiveness of the diminutive Schillaci–Baggio attacking duo, which complemented Vicini’s attractive playing style. Luca Vialli still had some success as a provider for Schillaci, however, assisting ‘Totò’s’ only goal of the match in the opening win against Austria in Rome with a cross. However, he later disappointed and missed a penalty in the following 1–0 victory against the United States, hitting the post after the keeper went the wrong way; it was ultimately playmaker Giuseppe Giannini who scored the winner to seal a passage to the next round, although Vialli was also still able to play a role in the goal, yet again demonstrating his vision and creativity with a clever dummy, letting Donadoni’s pass travel between his legs to meet the midfielder’s run, who then finished off a wonderful team move. With Vialli being rested for Italy’s final group match, Baggio was then given his first appearance of the tournament alongside Schillaci against Czechoslovakia, with both players performing well and scoring in the a 2–0 win. After remaining on the bench behind Schillaci and Baggio in Italy’s wins over Urugauy and Ireland in the round of 16 and quarter-finals respectively, with Totò proving to be decisive with his goals yet again, Vialli was later also at the centre of a controversial managerial decision. Vicini strikingly elected to start Vialli again in the semi-finals against the defending champions Argentina, led by the legendary Diego Maradona, at the San Paolo Stadium in Naples. The sudden change to the starting line-up was surprising to say the least, given Baggio’s form; Vicini reportedly told Baggio that he looked “tired,” and later commented that he didn’t regret the decision, however, as Baggio came off the bench and played part of the second half and all of extra-time. Although Vialli did play a role in Schillaci’s opening goal upon his return to the starting line-up, with the latter scoring off the rebound after goalkeeper Goychochea had parried Vialli’s initial shot, Luca, once again, did not have the best performance. Baggio, on the other hand, looked much more dangerous when he came on for him in the second half following Argentina’s fortunate equaliser from Claudio Caniggia, after goalkeeper Walter Zenga’s uncharacteristic error (this was the first goal Italy had conceded all tournament after setting a record unbeaten run); the Italian fantasista even came close to scoring from a free-kick, and played a role in Ricardo Giusti’s sending off. After Italy were eliminated on penalties (the only match of the tournament that Italy did not win), the decision not to start Baggio was criticised in the media. The former subsequently got the nod ahead of Vialli in Italy’s 2–1 victory over England in the bronze-medal match, and scored once again, along with his partner Schillaci. Vialli was subsequently excluded from the national team for several months. Following the tournament, Vialli went on to say that he had struggled with several fitness, physical, and health issues over the course of the summer of 1990, which negatively affected his form and his state of mind throughout the tournament. Many fans and pundits still do wonder whether Italy would have beaten Argentina in the semi-final, and even gone on to win the tournament over eventual champions West Germany had Baggio started alongside Schillaci, seeing as they combined so well, and when the former did have an impact and improve the team’s gameplay upon coming on. However, one does also wonder whether Vialli might have been able to discover his true form playing alongside his Sampdoria attacking ‘twin’ Mancini (not playing Mancini was a decision that Vicini did regret this time, however), and whether the two should have been given at least a chance to play together. Regardless of their missed opportunity at Italia 90, their unquestionable impact on Italian football, both as successful managers and two of Italy’s greatest forwards ever, will always be remembered, and the pair were rightly inducted into the Italian Football Hall of Fame in 2015.

In many ways, Vialli’s role in Italy’s Euro 2020 victory, as part of Mancini’s staff after such a long absence from the coaching world, symbolised a new opportunity for success that neither of the goal twins were truly given with Italy throughout their playing careers; this made their triumph all the more poetic and beautiful. Coincidentally, years after retiring from coaching, Vialli had actually expressed in a 2016 interview with Vanity Fair that he hoped, one day, to return to the world of management in a sports director role alongside Mancini. Seeing their bond on the sidelines, and their emotional, brotherly embrace after Italy defeated England in the penalty shoot-out in the Euro 2020 final at Wembley, a stadium associated with many important moments in his career, will always be a stand-out moment for me. Indeed, the one thing really lacking from Vialli’s career (not counting the Intercontinental Cup, seeing as he had left Juventus before being able to compete in the 1996 final victory against Riverplate) was a title with Italy, so it is fitting that he was finally able to capture some silverware for his country in a different role. After one of the darkest moments in the history of the Italian national team, which culminated in a humiliating failure to qualify for the 2018 World Cup under manager Giampiero Ventura (the first time Italy had failed to do so since 1958), the goal twins came to Italy’s rescue, and helped the team win the European Championship in style. Under the often pragmatic Mancini, Italy surprisingly played lovely, attacking football, scoring a personal best of 13 goals throughout the tournament, and also breaking several other records along the way, including setting a new international unbeaten streak (37 matches). Italy’s Euro 2020 victory under the goal twins, after the team’s struggles and Vialli’s illness, was the culmination of a wonderful friendship and a highly successful professional partnership, and it came to represent triumph over adversity. It is unfortunate that, only months after winning the European Championship, and subsequently finishing third in the 2020–21 UEFA Nations League finals, Italy rather surprisingly once again failed to qualify for the World Cup in 2022, after a shocking injury-time defeat to North Macedonia in the play-offs. However, while Mancini and his staff arguably are at fault to some degree for failing to keep the team’s emotions in check after winning Euro 2020, I’m not certain how much blame can truly be held against them; for example, in my opinion, many decisive errors in front of goal, such as Jorginho’s two penalty misses, had they been scored, would have seen Italy qualify directly as the top team in their group. After the goal twins’ shared disappointment at the 1990 World Cup, a successful World Cup campaign together on the sidelines would have done even more for the pair’s already incredible legacy. Considering that Vialli was fighting yet another battle with cancer during this time, it is incredible that he had the strength to remain in his role and support his dear friend, especially when Italy’s failure to qualify must have been all the more harrowing for him.

Forever Remembering a True Leader and a Gorgeous Soul

“I’m convinced that our children follow our example more than our words. I have less time to be that example, now that I know I won’t die of old age, so I try to be a positive example. I try to teach them that happiness depends on the perspective with which you look on life, that you shouldn’t put on airs, that you should listen more and speak less. Laugh often, help others. That’s the secret of happiness.”

Vialli in a 2022 interview with Netflix

Aside from being a champion in the truest sense, Vialli was a classy, gracious, and good–natured person, and a well-liked player, with a great sense of humour. Indeed, he was known for frequently pulling mischievous pranks, including a particularly infamous one involving Parmigiano cheese, which he reportedly played on Sacchi in 1992; the Italy manager at the time apparently did not approve of the joke, and it is speculated that the incident led to the deterioration of their relationship, with Vialli later being excluded from the national team, as mentioned above. Looking back on Vialli’s distinctive and likeable personality, what always amazed me about him, above all, however, was his courage, dignity, and spirit, even when discussing the terrible disease he was fighting; incredibly, he did not consider his struggle with the illness to be a battle, and even nonchalantly referred to the cancer as a “travel companion” that he would have rather avoided. To this day, it astounds me that he had the strength to see past his dreadful illness and reflect on all the wonderful important things he had in his life, and even remember the more humorous moments of his struggle. He was also a family man, of course, and a true gentleman of the game, who clearly made his mark on both Italian and English football. He left a wonderful impression on people wherever he went, not only because of his success, but also because of his values. And it was his fair-play and conduct, on top of his ability, which ultimately saw win the Premio Giacinto Facchetti in 2018.

Following Vialli’s untimely death in January, after his lengthy struggle with pancreatic cancer, countless players and managers paid homage to him on social media with emotional tributes; for example, his former Juventus teammate Roberto Baggio made a heartfelt post on social media, while his former Sampdoria teammate Graeme Souness described him as a “gorgeous soul.” Chelsea honoured his memory in their first match following his passing, against Crystal Palace, with a video tribute, which was shown on the Stamford Bridge Big Screen. Fans of his former club Sampdoria also made tributes in Vialli’s honour ahead of their next Seire A home match against Udinese, with the club’s president, Marco Lanna – Vialli’s former team-mate – also paying homage to him in a speech before the game. The FIGC celebrated his memory by announcing that a minute’s silence would be held before the upcoming Serie A matches, and by circulating a wonderful video compilation on Instagram, made of his speeches and words of motivation to the Italian national team throughout Euro 2020, and before the final in particular, as part of Mancini’s staff. From watching these snippets, it is really quite incredible to see how contagious his enthusiasm was, or how he could simply capture a room and commanded respect, even without raising his voice; to me, that is what true leadership is. It is therefore no surprise to me that Euro 2020–winner Federico Bernardeschi later commented that without Vialli’s presence, Italy would not have won the European Championship. Another wonderful anecdote associated with Vialli that comes to mind whenever I think of him was when he managed to relieve tension in the dressing room at Chelsea ahead of his first match as player-manager. He ingeniously gave glasses of champagne to his players before the second leg of their League Cup semi-final against cross–city rivals Arsenal during the 1997–98 season; Chelsea were able to overturn the first leg deficit with a 3–1 victory to advance to the final (with Vialli being named man of the match), eventually going on to win the title at Wembley. And of course, Vialli was as gracious as always even in victory, congratulating both his players and staff on the achievement, and even acknowledging the work of his predecessor, Ruud Gullit.

Gianluca is survived by his second wife, former model Cathryn White-Cooper (whom he married in London in 2003), and two daughters, Olivia and Sofia. He certainly left us too soon, and will be deeply missed by the entire footballing world, but the fond memories he left us with will always remain in our hearts.

Grazie di tutto, Luca!