There are some players who are synonymous with football. They not only played it professionally, but they lived and breathed it in the way that they won games and titles by completely dominating their opponents and entertaining fans simultaneously, leaving a lasting impression of them in our memories for years to come. One of those players was the late Edson Arantes do Nascimento, better known to the public as Pelé. In the first part of this article, I will examine Pelé’s playing career and his standing among the best footballers of all time.

Often nicknamed ‘O Rei‘ (‘The King,’ in Portuguese), Pelé’s technical and creative playing style was tied to the entertaining Brazilian style of football, which came to be known across the globe as ‘joga bonito‘ (literally ‘play beautifully,’ in Portuguese, even though the expression is surprisingly not actually used in Brazil) or ‘jogo bonito’ (‘beautiful game,’ in Portuguese). One of the most beloved and most influential players of all-time, Pelé was a highly prolific goalscorer, who had a successful club career with Santos, but he is known in particular among football fans for his performances with the Brazilian national side. Arguably the best player in World Cup history, he shone in several World Cups, becoming the only player ever, still to this day, to have won the World Cup three times, turning Brazil from perennial ‘nearly men’ (following the ignominy of the defeat to Uruguay in the final match of the 1950 World Cup at the Maracanã stadium in Rio de Janeiro, later dubbed the “Maracanazo“), into the greatest and most successful footballing nation in history, and establishing himself as a legendary figure in the history of football. With his incredible ability, and his exciting and unique playing style, he essentially brought an entire new meaning to the already well-known expression the “beautiful game,” which was popularised by Pelé himself, even though the phrase’s disputed origins and association with football purportedly date back even further.

Considered by many in the sport as one of the greatest players of all time, if not THE greatest, in 2000, FIFA named Pelé as the joint male Player of the Century, along with Argentine number 10 Diego Maradona. An incredible athlete, in addition to being a prolific, skilful, creative, and talented playmaker, Pelé also holds many footballing records:

- Although Pelé’s official goalscoring tally across all club and international competitions has been a source of dispute, with the official tally of 757 professional career goals circulating in the media (although certain sources report different totals; for example, Amnesis del fútbol, a fantastic Twitter account for football stats, records Pelé’s official goal tally as 756), including friendlies, he reportedly scored an astounding 1,279 goals in 1,363 games, a Guinness World Record.

- He also scored a record 92 hat-tricks in matches officially recognised by both FIFA and CONMEBOL.

- Unofficially, Pelé also reportedly tallied 368 career assists in competitive matches (although different sources have reported conflicting tallies, with Amnesis del fútbol reporting the tally as 363 assists), the second most ever behind Ferenc Puskás of Hungary with 404 (since assists have been officially recorded, it is Argentine number 10 Lionel Messi who has provided the most, with 353 as of 12 March 2023); 323 of these came at club level (the second most ever unofficially, after Dutch playmaker Johan Cruyff with 330), while the remaining 45 came with the Brazil national team.

As a creative, skilful, and prolific forward, Pelé was a complete and versatile player, who really had everything you would want in a player in his position, which allowed him to play anywhere across the front-line. He was often used in more of a supporting role, as a second striker alongside a true centre-forward, but was also capable of playing as an out-and-out striker, or even just behind the attack as an offensive playmaker, as was often the case in his later career. Although he might have lacked the all-round defensive skills of a talented, complete, and prolific utility player such as the legendary Argentine Alfredo Di Stéfano, Pelé was still elite in almost every aspect of the attacking game. He often functioned in a free offensive and creative role, roaming the attacking third, but also dropping deep to help win back the ball or link-up with his team-mates and create chances; he would even drift out wide to take on opponents in one on one situations, but was also capable of getting into the box to get onto the end of his team-mates deliveries and score himself. He was fast, explosive, agile, balanced, skilful, powerful, two-footed, and a fantastic athlete, who was incredible in the air, despite his diminutive stature, due to his outstanding elevation and heading ability, which allowed him to beat out larger players to the ball. He was also a fantastic dribbler, who had plenty of flair to his game, coupled with excellent ball control and technical skills, which enabled him to pull off spectacular moves. He was a remarkable finisher, both in open play, and from free kicks and penalties, which made him a highly prolific goalscorer, but he was also a hard-working player, who assisted his team defensively, and a highly creative playmaker, with excellent vision and passing ability, which made him a very productive assist provider for his teams. But beyond his qualities as a player, he was also known for his warm personality, class, sportsmanship, and fair-play, which, along with his skills, made him extremely popular among fans and players alike, and respected even among his opponents.

“Pelé was the most complete player I’ve ever seen, he had everything. Two good feet. Magic in the air. Quick. Powerful. Could beat people with skill. Could outrun people. Only five feet and eight inches tall, yet he seemed a giant of an athlete on the pitch. Perfect balance and impossible vision. He was the greatest because he could do anything and everything on a football pitch. I remember João Saldanha the coach being asked by a Brazilian journalist who was the best goalkeeper in his squad. He said Pelé. The man could play in any position”.

Legendary England defender Bobby Moore on Pelé

Pelé’s Early Life and Club Career

Pelé was born in the town of Três Corações, in the interior of Minas Gerais state, Brazil, on 23 October 1940, to João Ramos do Nascimento – also a footballer, better known as Dondinho – and Celeste Arantes. He was apparently named in part after Thomas Edison, which became Edson. His younger brother, Zoca, also pursued a footballing career, also playing for Santos, but not encountering a comparable level of success to Pelé. Pelé’s family moved around a lot in his youth due to his father’s own football career, until a knee injury put an abrupt ending to his dream. Pelé grew up in poverty in the city of Bauru, a railway town approximately 180 miles west of São Paulo. He helped out his family in his youth with several part-time jobs, including repairing and shining shoes and working in local cafés, while his mother worked as a maid, in addition to being a housewife. When he was a child, Pelé was initially known by the nickname “Dico.” Although various apocryphal origin stories exist for Pelé’s famous nickname, some of which are disputed, it is commonly reportedly believe that it arose when he mispronounced the name of his father’s Vasco teammate, a goalkeeper who was known as “Bilé,” whom the young Edson admired at the time; his classmates proceeded to mock him, thus endowing him with the nickname, which Pelé initially detested. Little did they know that this nickname would become one of the most widely recognised and revered names in footballing history.

Although Pelé’s mother was a major influence on him, as she encouraged him to pursue his dreams during his early career, she had initially disapproved of his dream to play football, as his father’s career had been cut short; he suffered a meniscal injury while playing for a local club in Baruru, São Paulo, and received no wages while injured, leading to the family’s financial struggles. It was Dondinho who taught Pelé how to play football, and who instilled his own passion for the game in his son. Rather astonishingly, the family reportedly could not afford a ball, and Pelé learned how to play football barefoot in the favelas, by using a rolled-up sock on the street, and also practised his ball-juggling skills with a grapefruit. Legend has it that following Brazil’s defeat to Uruguay in the final match of the 1950 World Cup on home soil, Pelé reportedly promised his distraught father that he would win the title for Brazil. Who knows how many, if any, believed that he would indeed accomplish such a feat only eight years later. A precocious talent, Pelé began to draw the attention of scouts, and at the age of 15, he joined São Paulo side Santos, after being noticed by Waldemar de Brito, who reportedly foretold that the young Edson would become the greatest player in the world. Pelé soon broke into the first team, scoring on his professional debut in a 7–1 victory against Corinthians in 1956, after coming off the bench in the second half. He finished his debut season as the league’s top scorer (specifically the 1957 Campeonato Paulista Blue Series, with 17 goals, in which Santos finished second; in total Pelé scored 36 goals, including the 19 netted in qualifying), a feat almost unheard of. He went on to conquer Brazil, South, America, and the world with the legendary Os Santásticos side of the 50s and 60s, which featured several other fantastic players, including the likes of forwards Pepe, Dorval, Mengalvio, and Coutinho, as well as iconic club captain Zito. During his remarkable club career, he won six Campeonato Brasileiro Série A/Taça Brasil titles (five consecutively between 1961 and 1965), among numerous other domestic titles with Santos, finishing as the competition’s top scorer in 1961, 1963, and 1964. Additionally, he won the 1962 and 1963 Copa Libertadores with Santos, the South American equivalent of the European Champion’s Cup (the predecessor to the current UEFA Champion’s League), as well as the 1962 and 1963 Intercontinental Cups. He was also named the South American Footballer of the Year Award in 1973 (the South American equivalent of the France Football Ballon d’Or/European Footballer of the Year Award), a prize which was first established in 1971 by newspaper El Mundo, after finishing in second place the previous year. His 643 official goals for Santos was a record for a single club (the tally has been disputed, however, with Santos including Pelé’s 448 goals in friendlies, and recording his club total as 1,091 goals, while Amnesis del fútbol reports his official goal tally for Santos as 642), which stood until it was broken by Messi of Barcelona in December 2020.

Conquering the World with Brazil

But despite his success with Santos, Pelé is certainly remembered in particular for his achievements with the Brazil national football team. Pelé’s international debut came only a year after his club debut, in a 2–1 defeat against rivals Argentina at the Maracanã on 7 July 1957 in the first leg of the Copa Roca, a match in which he also scored his first international goal, becoming Brazil’s youngest goalscorer ever at the age of 16 years and nine months.

It’s incredible to think that a knee injury almost ruled Pelé out of the 1958 World Cup the following year, and that it was also ultimately the young José Altafini’s injury which also gave Vavá the chance to play up-front with him, with the new attacking partnership shining throughout the rest of the tournament. The 19-year old Altafini, known as “Mazola” in Brazil (due to his resemblance to former Italian footballer Valentino Mazzola), had initially started up-front for Brazil in the first round of the 1958 World Cup ahead of the more experienced and prolific but less technical Vavá, until manager Vicente Feola replaced Mazola with Vavá following his injury in the second group match against England, and as he seemed to be suffering psychologically from the pressure of a high-profile move to Italian giants Milan. At only 17 years of age, Pelé was – at the time – the youngest player ever to take part at the tournament, and was part of a fantastic squad featuring a plethora of attacking talents, which included the likes of Garrincha, Vavá, Didi, Mário Zagallo, and Mazola, as well as the leadership of Zito, and the unrelated fantastic attacking full-back pair Djalma Santos and Nilton Santos; the team also made use of a revolutionary fluid 4–2–4 formation under Feola, and made headlines not only for its success, but also because of the beautiful football its players displayed. However, like Vavá, Pelé was also initially only meant to be a substitute, as he was still recovering from injury; ironically, the team’s psychologist, João Carvalhaes, even felt that Pelé was “obviously infantile,” and that he lacked “the necessary fighting spirit.” After breaking into the starting line-up, assisting Vavá’s second goal in a victory over USSR in the final first-round match, the young Brazilian number ten proved everyone wrong, and finished as the second highest goalscorer of the 1958 World Cup behind Just Fontaine of France, and was Brazil’s top goalscorer of the tournament, with six goals; these included the only goal of the match against Wales in the quarter-finals (making him the World Cup’s youngest goalscorer ever at the time), a hat-trick in the semi-final against France (in which he became the youngest player ever to achieve this feat), and two more in the final against hosts Sweden, as Brazil and Pelé won the match in style, prevailing 5–2, still to this day the highest-scoring World Cup final ever, and one of only three World Cup finals won by a three-goal margin.

After going down 1–0 to the hosts early in the first half of the final, thanks to lovely goal by the legendary Swedish playmaker Nils Liedholm, Brazil then equalised five minutes later with Vavà, who finished opportunistically after seemingly receiving the ball from Pelé inside the box, who looked to have knocked on a Garrincha cross (although this is debated by fans, even if FIFA credit him with an assist in the 1958 World Cup final). Vavà scored a similar second goal with just under 15 minutes left before half-time for Brazil to take the lead, putting away another Garrincha cross, who had dashed past his marker before putting in a low delivery, after receiving the ball from Pelé, who had played a cheeky back-heel pass to the winger from inside the box. Pelé then truly came to life in the second half, scoring twice, the first of which is widely regarded as one of the greatest goals of all-time; after out-jumping an opponent to control the ball with his chest inside the box, and then turning past his marker, he flicked the ball over another defender with an audacious ‘sombrero’, before volleying the ball into the bottom left-hand corner with his right foot. At the age of 17 years and 239 days, he became the youngest player ever to play and score in a World Cup final (and later the youngest player ever to win the title). Goals from Zagallo, for Brazil, and a consolation goal by Agne Simonsson, for Sweden, followed. Then, in the final minute of play, Pelé started the move for his second goal of the match, and the last goal of the final: he received the ball on the left flank, and played a clever lay-off to Zagallo with a back-heel flick, who then crossed the ball into the box; Pelé ran into the area and connected with the cross with an accurate header, to widen the gap even further, and give Brazil their first World Cup title ever. Following the match, Pelé was named the Best Young Player of the Tournament and was given the Silver Ball Award behind Didi, as the second best player of the 1958 edition of the tournament.

In the 1959 South American Championship the following year (the predecessor to the Copa América), Pelé shone for his country once again, and was named best player of the tournament, ending the competition as the top scorer with eight goals, although Brazil ultimately finished in second place behind Argentina by a single point, despite not losing a single match (at the time, the tournament format consisted of a single group).

By the time the 1962 World Cup in Chile had come around, Pelé was already widely regarded as the best player in the world, despite his young age, having just come off of a fantastic season with Santos. He started out the tournament strongly, with a stunning individual goal (in which he took on six players) and an assist in the opening 2–0 win against Mexico. However, he sustained an injury in the following group match against Czechoslovakia, which ruled him out for the remainder of the tournament. In his absence, Garrincha led the team to victory, earning Pelé his second World Cup medal, while Brazil became only the second team ever after Italy in 1938 to defend the title.

With Pelé in his physical prime, one would’ve expected another brilliant performance at the 1966 World Cup in England; however, it was a far less successful campaign, as Brazil shockingly went out in the first round. Although Pelé scored with a free kick in the opening 2–0 win against Bulgaria, becoming the first Brazilian player ever to score in three consecutive World Cups (a record since matched by Ronaldo and Neymar), the aggressive defending saw him sustain an injury, which ruled him out of the second match against Hungary, which ended in a 3–1 defeat. In the final group match against Portugal, Pelé returned to the starting line-up, but was still hampered by injury as Brazil suffered another 3–1 defeat, although the refereeing was later brought into question due to a harsh foul on the Brazilian number 10 by João Morais, who was not sent off, which left Pelé limping and unable to come off as substitutes were not allowed at the time. Once again, injury had hindered Pelé, even though he had still managed to demonstrate his ablity and importance to his team when he was fit.

“I thought that was a goal.” – Pelé

“You and me both.” – Gordon Banks.

“You’re getting old, Banksy, you used to hold on to them.” – Bobby Moore.

The famous exchange between Pelé, Bobby Moore, and Gordon Banks following the latter’s ‘Save of the Century‘ on Pelé in the group match between Brazil and England at the 1970 World Cup

The ageing Pelé was initially reluctant to take part in another World Cup with Brazil, in part after being investigated by the Brazilian military dictatorship for left-wing sympathies in 1969. However, he went on to win the 1970 edition of the tournament in Mexico as one of the team’s key players and leaders, as the offensive fulcrum of a star studded side that is now considered one of the greatest teams of all-time. Now in the twilight of his career, he played in a deeper more central creative role in Brazil’s lethal front-five under manager Zagallo (Pelé’s former international teammate in both the 1958 and 1962 World Cup victories), which also included Jairzinho, Gerson, Tostão, and Rivelino. On top of the goals he scored and assists he provided, he was also involved in many other memorable moments which are still spoken of to this day. For example, in the opening match against Czechoslovakia, although he scored the match-winning goal in an eventual 4–1 victory (making him the first player ever to score in four different World Cups), he is mostly remembered for almost scoring a stunning second goal with a clever lob over keeper Ivo Viktor from just behind the half-way line; however, unfortunately his shot just missed the target, robbing us of a spectacular goal. Pelé also recorded an assist during the match, providing the final pass for Jarzinho’s second goal, which the Brazilian number seven scored with a well-placed, thunderous low effort at the far post, taken from just inside the box, after a lovely individual run. In the second group match against defending champions England, Pelé had a powerful header stopped by the legendary goalkeeper Gordon Banks, who produced an incredible, acrobatic reaction save, diving to the bottom-right corner of his goal to somehow tip the ball over the bar; the miraculous stop later became known as Banks’s so-called “Save of the Century.” Pelé once again proved to be decisive, however, later assisting Jairzinho’s only goal of the match. He then scored twice in a 3–2 win over Romania in the final group match.

In the quarter-finals against Peru, Brazil and Pelé once again put in another dominant display, with the number ten unlucky not to score during the match, although he still helped set-up the first of Tostão‘s two goals, who tapped the ball into an empty net after the keeper couldn’t hold on to Pelé’s low cross–shot. Another one of Pelé’s most memorable plays during the tournament was his trademark “drible de vaca” feint against Uruguayan keeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz in the semi-final, where he made his famous “runaround move“: Pelé beat the defence to run onto Tostão’s throughball, and then rounded the on-rushing keeper without actually touching the ball; Pelé feigned controlling the pass on the run, when he actually let the ball slide past the left side of the befuddled shot-stopper, while he instead ran past him to his right, collecting the ball on the other side of the keeper. However, unfortunately Pelé then shockingly missed the target, shooting just wide of the far post while off balance. He made up for the miss, however, by later assisting Rivelino for the final goal of the match in an eventual 3–1 victory.

“How do you spell Pelé? Easy: G-O-D.”

Paddy Crerand on Pelé as part of the ITV panel during the 1970 World Cup

Pelé and Brazil followed up this performance with a memorable resounding 4–1 victory over reigning European Champions Italy in a classic final at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City. Pelé was in stunning form, and assisted twice during the match (including the lay-off for Carlos Alberto’s iconic late goal, finishing off a brilliant team move which bamboozled the demoralised Italian defence, which was clearly showing signs of fatigue after the exciting 4–3 extra-time victory over West Germany in the semi-final, which was later dubbed the ‘Game of the Century‘); he also scored the opening goal of the match, beating goalkeeper Enrico Albertosi at the near post with a stunning and accurately placed header while off-balance, after out-jumping legendary Italian defender Tarcisio Burgnich. After scoring, Pelé’s memorable and ecstatic celebratory embrace with teammate Jairzinho, who lifted him up, became one of the defining images of the tournament. The Italian full-back later commented on the goal, and Pelé’s performance in the final with an iconic quote:

“I told myself before the game, he’s made of skin and bones just like everyone else – but I was wrong.”

Renowned Italian defender Tarcisio Burgnich on Pelé after Italy’s 4–1 defeat to Brazil in the 1970 World Cup Final

His goal in the 1970 World Cup meant that the had scored in two different Wold Cup finals, after scoring a brace in the 1958, bringing his goal tally in World Cup finals up to 3. Pelé won the Golden Ball Award as the tournament’s best player. His impressive performances throughout the competition are also evident when analysing his statistics:

- Pelé made a total of 10 direct goal contributions throughout the tournament in terms of goals (4) and assists (6).

- With his 10 goal contributions, he was therefore also directly responsible for approximately 53% of Brazil’s 19 goals throughout the tournament.

- Brazil’s 19 goals are the second-most total goals ever scored by a World Cup–winning side after Germany in 1954, with 25.

- Brazil’s 4–1 victory over Italy in the 1970 World Cup final is one of only three World Cup finals to have been won by a three–goal margin; the other two finals, coincidentally, are 1958 (in which Pelé also featured, a 5–2 win against hosts Sweden) and 1998 (in which Brazil suffered a 3–0 defeat to hosts France), which also involved Brazil.

- Pelé made a single tournament record of 6 assists during the 1970 World Cup (according to some sources, this number ranges between 5 and 7, however).

Pelé’s last international appearance came on 18 July 1971 in a match against Yugoslavia in Rio de Janeiro. With 77 goals in 92 appearances, he is Brazil’s all-time top goalscorer, alongside Neymar. He was also the highest–scoring South American international male footballer of all time for several decades, until he was overtaken by Messi in 2021.

At the World Cup, Pelé holds numerous records and significant achievements, which make him arguably the greatest player in the history of the tournament:

- With goals in both the 1958 and 1970 World Cup finals, Pelé is one of only five male players, along with Vavá (Brazil – 1958 and 1962), Paul Breitner (Germany – 1974 and 1982), Zinedine Zidane (France – 1998 and 2006), and most recently Kylian Mbappé (France – 2018 and 2022), to score in two World Cup finals.

- Along with Vavá, Geoff Hurst (England – 1966), and Zidane, Pelé also held the record for the most goals scored by a male player in World Cup final matches (3), before it was broken by Mbappé in 2022 (4).

- Pelé made 14 appearances for Brazil across four tournaments, and is one of only five players to have scored in four World Cups, with only Portugal’s Cristiano Ronaldo having scored in more editions of the tournament (5).

- He has won the FIFA World Cup title an unprecedented three times.

- In total, Pelé scored 12 World Cup goals across four tournaments, the second most by a Brazilian player, after Ronaldo with 15, making him the sixth-highest goalscorer in World Cup history.

- With a hat-trick in the 1958 World Cup semi-final victory against France, Pelé became the youngest player ever to achieve this feat at the age of 17 years and 234 days.

- At the age of 17 years and 239 days, he is the youngest player ever to play and score in a World Cup final, and to win the title.

- Pelé has also provided an all-time record 10 assists in the tournament (some sources record his assists as being 8, however, a record he shares with Messi and Maradona; FIFA only began to record official assists starting from the 1966 World Cup; officially he has 8 OPTA World Cup assists).

- His 6 assists in the knock-out stages is also a World Cup record, which he shares with Messi.

- He also assisted in three editions of the tournament, a feat only bettered by Messi (5).

- He has also provided the most assists in World Cup finals (3 – 1 against Sweden in 1958, and 2 against Italy in 1970; according to some sources, he only provided 2 in the 1970 final, however).

- Pelé made a single tournament record of 6 assists during the 1970 World Cup (according to some sources, this number ranges between 5 and 7, however).

- Behind only Messi (21), Pelé officially has the joint–second–most direct goal contributions in World Cup history, with 20 (12 goals and 8 assists), alongside German strikers Gerd Müller (14 goals and 6 assists) and Miroslav Klose (16 goals and 4 assists), as well as compatriot Ronaldo (15 goals and 5 assists); if we take into consideration his alternate recorded tally of 10 assists, then his total goal contributions would be an all-time record of 22.

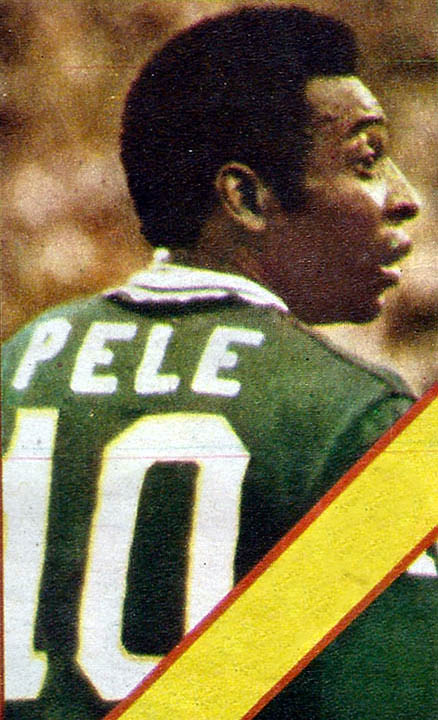

As mentioned earlier, Pelé eventually closed out his career with the New York Cosmos in the North American Soccer League, joining the team in 1975, and being named the Most Valuable Player of the 1976 NASL season. He also won the 1977 SoccerBowl in his final season, as part of a star-studded side which also featured the likes of the brilliant Brazilian right-back Carlos Alberto, legendary German sweeper Franz Beckenbauer, and the prolific Italian centre-forward Giorgio Chinaglia. In total, he officially scored 37 goals in 64 NASL matches, although his total tally for New York Cosmos is disputed by IFFHS, as the NASL did not always fully abide by FIFA regulations. A testimonial match was organised between his two former clubs Santos and New York Cosmos to mark his retirement in 1977, with Pelé playing a half for each side.

The Greatest Ever?

“This debate about the player of the century is absurd. There’s only one possible answer: Pel[é]. He’s the greatest player of all time, and by some distance I might add.”

Former Brazilian star playmaker Zico (often known as “the White Pelé” in the media) on Pelé

In men’s football, there are normally countless debates among pundits and fans over who was the greatest player of all time, with each fan arguing for one over another. The multitude of competitions – both club and international – in comparison to other male sports, in which the vast majority of world talents play in one league in North America, and the number of different roles and playing styles, and the changes that the game has undergone throughout the ages has made it almost impossible to choose a clear G.O.A.T. (“greatest of all time”). I unfortunately never saw past male footballing legends often included in this debate, such as Pelé, but also the aforementioned Maradona, Platini, Cruyff, Garrincha, Beckenbauer, Di Stéfano, and Puskás, or even the likes of George Best (Northern Ireland), Giuseppe Meazza (Italy), and Stanley Matthews (England), etc. so I can’t really compare them to those I’ve seen, even through statistical–historic research, or by watching footage of these players. It’s simply not the same, especially when it comes down to the “eye test” argument and assessment, which is already quite subjective, albeit important. Of those male players that I have seen, the ones who really have stood out to me are Romário (Brazil), Zidane, Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, Cristiano Ronaldo, and Messi, the latter of which, with his 2022 World Cup victory, is probably the greatest male player I have ever seen, while Brazilian number 10 Marta is probably the best female player I’ve personally watched. Each of these players has stood out across various club and international competitions, and won individual awards, or broke records, and combined a natural ability with big goals that won their teams major titles. Any one of them would have an argument for being the best of all time in all honesty, although I realise that some would disagree, and it’s hard to remain neutral and put our biases aside in these debates. Goals and statistics, while they aren’t the only important thing, certainly do matter significantly in assessing a player, certainly to a larger extent than what many of us football enthusiasts would hope, which is why unfortunately we often seem to be biased towards more offensive–minded players in these debates. This is particularly evident with our reverence of the creative advanced playmaker or number 10 role between the midfield and forward lines, which Pelé himself occupied, albeit in a more offensive manner than other 10s like Maradona. This is arguably the most iconic position in world football history, with many of these players being contenders for the title of the greatest of all-time. The number 10 role is arguably the most unique and respected role because it combines numerous qualities that we hold in high regard in football – technical skill, creativity, playmaking, and goalscoring – all into one role, and Pelé was certainly one of the very finest in this position, if not THE best.

Indeed, it seems that this view is held by many in the sport. In 1999, Pelé was elected ‘Player of the Century’ in a poll by France Football‘s past Ballon d’Or winners. The magazine later also issued a revised Ballon d’Or–winner’s list in 2016 to include non–European players as well, who were not eligible for the European Footballer of the Year award at the time (the regulations were changed in 1995 to include non–European players, and once again to include footballers playing outside of Europe in 2007); this ranking would’ve seen Pelé win the prize a record seven times (a feat matched only by Lionel Messi in 2021). Moreover, in 2013, FIFA awarded the Brazilian number ten with an honourary Ballon d’Or for his incredible career achievements (in 2010, the France Football Ballon d’Or and the FIFA World Player of the Year Award were temporarily merged into the FIFA Ballon d’Or Award, until 2015). Pelé was therefore publicly recognised as the best male footballer ever by both journalists and fellow footballers.

“The greatest player in history was Di St[é]fano. I refuse to classify Pel[é] as a player. He was above that.”

Legendary Hungarian forward Ferenc Puskás on Pelé

Although Pelé is mainly known for his exploits and success with Brazil at the World Cup, which cemented his legacy among the very best footballers ever, he also had a successful and record-breaking club career with Santos. Unfortunately, however, despite his undisputed technical ability, all the goals he scored and created, and the titles he won with Santos, there often persists a sort of Euro-centric, colonial revisionism when it comes to him and how his achievements are retroactively viewed, which seems to hinder his reputation as arguably the greatest player of all time. In particular, the fact that he never played in Europe is often brought up against him, despite the fact that all of Brazil’s players in the three World Cups he won played in their home-country’s domestic leagues. It was only in the 80s that top Brazilian players such as Zico, Falcão, and Socrates, as well as many others, really started moving abroad to play in Europe (in Italy, in particular), which led to the league’s gradual decline, and its incorrect perception as having always been weaker than the top European leagues. However, as Tim Vickery notes in a 2023 article for ESPN:

“Throughout Pel[é]’s career, today’s gulf between club football in Europe and South America simply did not exist. The South American game was at least as strong — as Pel[é] himself proved when he ran riot against Benfica in 1962 — and there was no financial chasm between the two continents, which is a modern development as a consequence of global TV revenue.”

Tim Vickery, ESPN, 2023

In fact, it should be remembered that a top striker like José Altafini, or Mazola as he was known in Brazil, was excluded from the Brazilian national side following his move to Italy after the 1958 World Cup, and even went on to play for Italy at the 1962 World Cup due to his Italian heritage. Contrary to popular belief, this was not due to Pelé’s explosion in the previous World Cup, as Altafini was more of an out-and-out striker, like Vavá, whereas Pelé was more of a creative second striker, albeit a highly prolific one. Although it could be argued that Altafini would not have started due to Vavá’s presence in the 1962 World Cup side, after he had already successfully taken Altafini’s place in the knock-out rounds of the 1958 tournament, leading Brazil to the title alongside the young Pelé, Pelé missed most of the tournament in Chile due to injury, which might have given Altafini an opportunity in a different role. Moreover, Altafini would have undoubtedly started in almost any other national side, as he was a successful and fantastic player in his own right, being a very well-rounded striker and a prolific goalscorer himself, as demonstrated by the fact that he was chosen to represent a major footballing nation such as Italy. Notwithstanding the fact that Altafini’s meagre contribution was eclipsed by Vavá and Pelé’s fantastic showing in the knock-out stages in 1958, he still managed two goals when he initially started in the opening first round 3–0 victory against Austria, in addition to contributing to Pelé’s goal against Wales in the quarter-finals. During his time in Italy, he had a fantastic club career both domestically and continentally, and was highly successful and prolific, as demonstrated by his achievements:

- Altafini went on to win four ‘scudetti’ (league titles) during his time in the Italian Serie A (2 with Milan and 2 with Juventus).

- Altafini also won the 1962–63 European Cup with Milan, scoring two goals in the final victory against Benfica.

- Altafini was the top scorer of the 1962–63 European Cup with a then record 14 goals, including a record five goals in Milan’s 8–0 win over l’Union Luxembourg in the first leg of the round of 16.

- Altafini won the capocannoniere title in Milan’s 1961–62 scudetto victory, with 22 goals; this title is awarded to the league’s top goalscorer.

- Altafini scored a total of 216 goals in Serie A during his time in Italy, making him the joint-fourth-highest goalscorer of all time in the league, along with the incredible Italian fantasista Giuseppe Meazza.

Considering all of these fantastic achievements, the fact that Altafini still was not able to find a place in the legendary homegrown Brazil squad of the early 60s is a testament to the strength of the Brazilian league system at the time, which demonstrates how good Pelé truly was, as both the Brazilian national team’s key player and the best player in the Brazilian championship.

Moreover, while it has been argued that Pelé played in an era which was athletically less demanding, and it has been noted that some of Pelé’s goalscoring records and performances have been exaggerated, and that he was fortunate to have many fantastic teammates both with Brazil and Santos, he was still very prolific and successful at club level, not only domestically, but also continentally and internationally in official competitions. And while he did not win his titles on his own, he certainly stood out among his peers, which is particularly impressive given the quality of the sides he played in. Moreover, it should be noted that many other legendary figures of the game, such as Cristiano Ronaldo, Messi, Zidane, Ronaldo, Puskás, Cruyff, or Di Stéfano, also played in iconic club or international sides, yet this does not detract from what they have achieved, as regardless, they were highly skilful and talented footballers who played a key role in winning titles for their teams, and who delivered some truly iconic moments when it mattered most. Furthermore, even though matches were slower paced during his career, Pelé also admittedly encountered a level of aggression from his opponents (as was the case at the aforementioned 1966 World Cup, for example) that the leading contemporary footballers fortunately would not face, as today they are more protected by match officials; in fact, penalty cards were only first introduced to punish players for bad fouls at the 1970 World Cup, towards the end of Pelé’s career, and in his final edition of the tournament. There are also additional popular apocryphal posts circulating on social media, which seem to be aimed at discrediting Pelé’s achievements even further. One of these is the rumour that Pelé played in an era in which the offside rule did not exist, which aided in inflating his goalscoring statistics; this is in fact false. The offside rule was first established in 1863, and was actually more strict during Pelé’s career. Moreover, although some fans have even attempted to argue that Pelé’s record-breaking goalscoring feats were only due to the fact that he also played in an era where goalscoring rates were significantly higher, Adam Bate of Sky Sports News actually noted in 2022 that a statistical comparison between his era and the modern game demonstrates that this was not truly the case:

“The average number of goals per game scored in Brazil’s national championship between 1961 and 1965 was 3.07. The average number of goals per game in the last five years of the Champions League is 3.02 – very similar.”

Adam Bate, Sky Sports News, 2022

Although Pelé did not get many opportunities to face-off against major European club sides in competitive matches, it should also be noted that when he was able to, he did still beat out top European Cup winning sides such as Benfica of Portugal and Milan of Italy in the 1962 and 1963 Intercontinental Cups respectively. Furthermore, he won these titles after also winning the Copa Libertadores against leading South American sides Peñarol and Boca Juniors, thus earning Santos the titles of both ‘South American’ and ‘world champions.’ The fact that he only won the Copa Libertadores twice throughout his club career has also been used on social media as a means of questioning his achievements; however, it should be noted that following these victories, Pelé did not compete in the competition as frequently with Santos, taking part only once more in 1965, where they reached the semi-finals, with Pelé finishing as the top-scorer with eight goals. The reason behind this was that it was more lucrative at the time for the club to embark on international tours. During these international tours with Santos, however, he did also star in friendly victories and closely–fought encounters against several leading European sides, including Inter, Roma, Benfica, Real Madrid, and Barcelona, among others. Although todays fans might understandably readily dismiss these results, as they came about in mere friendlies, it should be noted that at the time, given the fact that South American and European club sides scarcely competed against one another, these were no ordinary friendlies; indeed, they were highly competitive matches, featuring many starters, and which were played in front of packed stadiums, with crowds who flocked to see Pelé, the best player in the world.

One of my favourite Twitter accounts for football stats, VisualGame has also demonstrated in a wonderfully detailed thread on Pelé just how incredible Pelé’s attacking output was in comparison to other all-time greats, with an astounding 756 goals and 367 assists in 795 full official games (special thanks also go out to @Trachta10 and @pelesburner for their fantastic work in researching assist statistics for past players and sharing them with the rest of football twitter), with a rate of 1.41 goal contributions per 90 minutes. Moreover, in 130 matches against European sides, Pelé scored an incredible 144 goals!

“I sometimes feel as though football was invented for this magical player.”

Celebrated England midfielder Bobby Charlton on Pelé

What Pelé achieved on the pitch can never be taken away from him. He came up against the best and won everything with a beautiful, technical, and creative style which revolutionised and transcended mere football, transforming the beautiful game into living art. His combination of skill, athleticism, and goalscoring allowed him to set some incredible records, which either stood for a long time or have still yet to be broken, and also enabled him to produce some truly iconic moments which will forever be remembered in the annals of football history. He is the definition of a footballing legend, and one of the very best players ever, if not THE best, and his name will be uttered with the same degree of reverence among football fans even decades from now.

This concludes the first part of this article; in the second part, I will examine Pelé’s life off the pitch and analyse his influence and significance beyond the beautiful game.

The best my dad was on the cosmos , pele was a nice man I was only 4 maybe 5 when I met him .

LikeLiked by 1 person